What is Heat Transfer? Comprehensive Guide

Heat transfer is a fundamental process governing energy exchange between systems at different temperatures. It plays a crucial role in countless natural phenomena and engineering applications, from the warming of the Earth by the sun to the cooling of electronic devices. Understanding its principles is essential for designing efficient and reliable systems across various industries. This blog post will delve into the intricacies of heat transfer, exploring its different modes, governing equations, and practical applications. We’ll also highlight the crucial role of Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) in analyzing and optimizing heat transfer processes, particularly using powerful software like ANSYS (What is Ansys?). As experts in CFD consulting and services at MR CFD, we aim to provide a comprehensive guide to this fascinating field.

Understanding the basics of heat transfer is crucial for any engineer, as it dictates the design and performance of countless systems. Let’s delve deeper into the fundamental mechanisms driving this essential process.

Heat Transfer Fundamentals: Conduction, Convection, and Radiation Explained

Heat transfer occurs through three primary mechanisms: conduction, convection, and radiation. These mechanisms often work in concert, but understanding them individually is crucial for effective thermal management in a wide range of engineering applications.

Conduction:

Conduction involves the transfer of thermal energy within a material or between materials in direct contact. This transfer is driven by temperature differences at the molecular level. Microscopically, higher temperature regions have molecules with greater kinetic energy. These molecules collide with their less energetic neighbors, transferring some of their kinetic energy and thus propagating heat through the material. The rate of heat transfer by conduction is governed by Fourier’s Law, which states that the heat flux is proportional to the temperature gradient and the material’s thermal conductivity.

- Key Characteristics:

- Occurs in solids, liquids, and gases, but is most dominant in solids.

- Direct physical contact or within a single material is required.

- Driven by temperature gradients within the material.

- Examples:

- A metal spoon heating up in a hot cup of coffee.

- Heat transfer through a wall on a cold day.

- Heat spreading through a metal heat sink in electronics.

| Material | Thermal Conductivity (W/m·K) |

| Copper | 401 |

| Aluminum | 237 |

| Steel | 50 |

| Glass | 1.05 |

| Air | 0.024 |

Convection:

Convection involves the transfer of heat through the movement of fluids (liquids or gases). This movement can be natural, driven by density differences due to temperature variations (e.g., warm air rising), or forced, driven by external means like fans or pumps. Convection is a more complex process than conduction, involving both the diffusion of heat at the molecular level and the bulk motion of the fluid.

- Key Characteristics:

- Occurs in fluids (liquids and gases).

- Involves bulk fluid motion.

- Can be natural (buoyancy-driven) or forced (externally driven).

- Examples:

- Boiling water in a pot (natural convection).

- Air cooling a computer chip with a fan (forced convection).

- Ocean currents distributing heat around the globe (natural convection).

Radiation:

Radiation is the transfer of heat through electromagnetic waves. Unlike conduction and convection, it doesn’t require a medium for propagation and can occur even in a vacuum. The rate of radiative heat transfer is governed by the Stefan-Boltzmann Law, which states that the heat flux is proportional to the fourth power of the absolute temperature.

- Key Characteristics:

- Does not require a medium for propagation.

- Transfer of energy through electromagnetic waves.

- Dependent on the temperature and surface properties of the emitting body.

- Examples:

- Heat from the sun reaching the Earth.

- Heat radiating from a fireplace.

- Infrared cameras detecting heat signatures.

Understanding these three modes of heat transfer is essential for tackling complex engineering challenges. From designing efficient heat exchangers to ensuring the thermal stability of spacecraft, these fundamental principles form the bedrock of thermal management. Now, let’s explore each mode in greater detail, starting with conduction.

Conduction: Microscopic View & Engineering Applications

At the microscopic level, conduction involves the transfer of kinetic energy between adjacent molecules or atoms. In solids, this occurs through lattice vibrations and the movement of free electrons. The rate of heat transfer by conduction is governed by Fourier’s law, which states that the heat flux is proportional to the temperature gradient and the material’s thermal conductivity. Materials with high thermal conductivity, like metals, transfer heat more readily than those with low thermal conductivity, like insulators. This understanding of material properties is crucial for making informed decisions in engineering design, which can be further enhanced with CFD services. You can explore more about material properties and their impact on CFD simulations in our blog post about.

From selecting the right materials for heat sinks in electronics to designing insulation for buildings, understanding conduction is paramount. Now, let’s turn our attention to convection, another crucial mode of heat transfer.

Convection: Natural vs. Forced – Mastering the Flow

Convection is the transfer of heat through the bulk motion of fluids (liquids or gases). This dynamic process is significantly more complex than conduction, influenced by a multitude of factors including fluid properties, temperature gradients, and flow geometry. Understanding the nuances of convection is crucial for optimizing a wide range of systems, from HVAC systems to chemical reactors and electronic cooling. Convection can be broadly classified into two categories: natural and forced.

Natural Convection:

Natural convection arises from density differences within a fluid caused by temperature variations. When a fluid is heated, it expands, becomes less dense, and rises. Cooler, denser fluid then replaces the rising fluid, establishing a circulatory flow pattern. This buoyancy-driven flow is responsible for many natural phenomena, such as the rising plume of smoke from a fire or the circulation of air in the atmosphere. The driving force in natural convection is gravity acting upon the density variations.

- Key Characteristics:

- Driven by buoyancy forces due to density differences.

- No external driving force (e.g., fan or pump).

- Heat transfer rate is generally lower than forced convection.

- Highly dependent on the gravitational field.

- Examples:

- Heating a room with a radiator.

- Cooling of electronic components in open air.

- Formation of atmospheric weather patterns.

- Factors Affecting Natural Convection:

- Gravitational acceleration (g)

- Coefficient of thermal expansion (β)

- Temperature difference (ΔT)

- Fluid properties (viscosity, thermal conductivity)

Forced Convection:

Forced convection occurs when an external force, such as a fan, pump, or wind, drives the fluid motion. The flow is not reliant on density differences and can occur even in isothermal conditions. Forced convection typically results in higher heat transfer rates compared to natural convection due to the enhanced fluid motion. A prime example is the cooling system in a car engine, where a pump circulates coolant to remove heat from the engine block.

- Key Characteristics:

- Driven by an external force (fan, pump, wind).

- Independent of buoyancy forces.

- Higher heat transfer rates compared to natural convection.

- Flow can be controlled and directed.

- Examples:

- Cooling of electronics with fans.

- Air conditioning systems.

- Liquid cooling systems for high-performance computers.

- Factors Affecting Forced Convection:

- Fluid velocity (V)

- Fluid properties (viscosity, thermal conductivity)

- Geometry of the flow path

- Surface roughness

| Feature | Natural Convection | Forced Convection |

| Driving Force | Buoyancy (density differences) | External force (fan, pump, etc.) |

| Flow Rate | Relatively low | Relatively high |

| Heat Transfer Rate | Lower | Higher |

| Controllability | Limited | Highly controllable |

| Dependence on Gravity | Significant | Negligible |

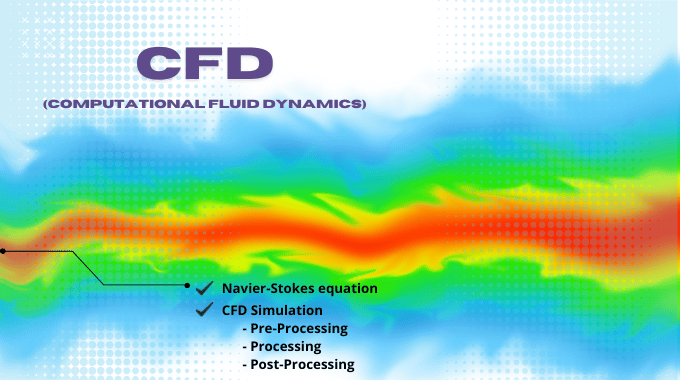

What is CFD Simulation in Heat Transfer?

for explain “What is CFD?“, We say that CFD Simulation is an invaluable tool for understanding and predicting the complex flow patterns and heat transfer characteristics in both natural and forced convection scenarios. It allows engineers to visualize temperature distributions, velocity fields, and other critical parameters, facilitating the optimization of designs for enhanced thermal performance.

Mastering the nuances of convection is crucial for optimizing a wide range of systems. Moving on, let’s shed light on the third mode of heat transfer: radiation.

Radiation: The Electromagnetic Heat Transfer

Radiation is the only mode of heat transfer that doesn’t require a medium for propagation. It involves the emission and absorption of electromagnetic waves. All matter with a temperature above absolute zero emits thermal radiation. This energy transfer occurs through photons, discrete packets of electromagnetic energy, traveling at the speed of light. Understanding radiation is crucial in diverse applications ranging from the design of solar panels and spacecraft thermal control systems to the analysis of thermal radiation in combustion processes and furnace design.

Key Principles of Radiative Heat Transfer:

- Electromagnetic Spectrum: Thermal radiation occupies a portion of the electromagnetic spectrum, primarily in the infrared region. The wavelength and intensity of the emitted radiation depend on the temperature of the emitting body.

- Emission: All bodies emit thermal radiation. The rate of emission is governed by the Stefan-Boltzmann Law, which states that the radiative heat flux is proportional to the fourth power of the absolute temperature and the emissivity of the surface.

- Absorption: When radiation strikes a surface, a portion of it is absorbed, increasing the internal energy of the absorbing material. The absorptivity of a surface quantifies its ability to absorb incident radiation.

- Reflection: Some portion of the incident radiation may be reflected away from the surface. Reflectivity is the fraction of incident radiation that is reflected.

- Transmission: In some materials, radiation can pass through. Transmissivity is the fraction of incident radiation that is transmitted through the material.

Stefan-Boltzmann Law:

The Stefan-Boltzmann Law is a fundamental equation in radiative heat transfer, describing the power radiated from a blackbody. A blackbody is an idealized object that absorbs all incident radiation. The law is expressed as:

q = σ * ε * T⁴

Where:

- q is the radiative heat flux (W/m²)

- σ is the Stefan-Boltzmann constant (5.67 x 10⁻⁸ W/m²·K⁴)

- ε is the emissivity of the surface (ranging from 0 to 1, where 1 represents a perfect blackbody)

- T is the absolute temperature (K)

Factors Affecting Radiative Heat Transfer:

- Temperature: The temperature of the emitting body is the most significant factor influencing the rate of radiative heat transfer.

- Surface Emissivity: Emissivity represents how effectively a surface emits radiation compared to a blackbody. Dark, rough surfaces typically have higher emissivities than light, smooth surfaces.

- Surface Area: The larger the surface area, the greater the radiative heat transfer.

- View Factor: The view factor represents the fraction of radiation leaving one surface that directly strikes another surface.

Applications of Radiative Heat Transfer:

- Spacecraft Thermal Control: In the vacuum of space, radiation is the dominant mode of heat transfer. Spacecraft thermal control systems rely on radiative heat exchange to maintain acceptable temperatures for sensitive equipment.

- Furnace Design: Furnaces utilize radiative heat transfer for efficient heating processes. Understanding radiation principles is crucial for optimizing furnace design and performance.

- Solar Thermal Systems: Solar collectors absorb solar radiation and convert it into thermal energy for various applications, such as water heating and electricity generation.

- Infrared Thermometry: Infrared cameras measure the intensity of thermal radiation emitted by objects to determine their temperature.

| Property | Description |

| Emissivity (ε) | Measure of a surface’s efficiency in emitting thermal radiation (0 ≤ ε ≤ 1) |

| Absorptivity (α) | Measure of a surface’s efficiency in absorbing thermal radiation (0 ≤ α ≤ 1) |

| Reflectivity (ρ) | Measure of a surface’s efficiency in reflecting thermal radiation (0 ≤ ρ ≤ 1) |

| Transmissivity (τ) | Measure of a surface’s efficiency in transmitting thermal radiation (0 ≤ τ ≤ 1) |

From the design of solar panels to the analysis of thermal radiation in combustion processes, understanding radiation is essential. Now, let’s explore the concept of heat transfer coefficients, a crucial parameter in engineering calculations.

Heat Transfer Coefficients: The Heart of Engineering Calculations

Convective heat transfer coefficients (h) are fundamental parameters in thermal analysis and design, quantifying the rate of heat transfer between a fluid and a solid surface. They play a crucial role in the design and optimization of heat exchangers, electronic cooling systems, HVAC systems, and any application involving convective heat transfer. Essentially, the heat transfer coefficient represents the thermal conductance of the boundary layer between the fluid and the solid. A higher heat transfer coefficient signifies a more effective heat exchange, allowing for a greater heat transfer rate for a given temperature difference.

Defining the Heat Transfer Coefficient:

Newton’s Law of Cooling provides the defining equation for the convective heat transfer coefficient:

q = h * A * ΔT

Where:

- q: Heat transfer rate (Watts, W)

- h: Convective heat transfer coefficient (Watts per square meter Kelvin, W/m²·K)

- A: Surface area for heat transfer (square meters, m²)

- ΔT: Temperature difference between the fluid and the solid surface (Kelvin, K)

Determining Heat Transfer Coefficients:

Determining accurate heat transfer coefficients is crucial for predicting and optimizing thermal system performance. Two primary approaches exist:

- Experimental Methods:

These methods involve directly measuring temperature differences and heat fluxes in controlled experiments. Various experimental techniques are employed:

- Thermocouples: Measure temperature at specific points on the solid surface and within the fluid.

- Heat Flux Sensors: Directly measure the heat flux through the solid surface.

- Infrared Thermography: Provides a non-invasive way to measure surface temperature distributions.

- Liquid Crystal Thermography: Uses temperature-sensitive liquid crystals to visualize surface temperature variations.

| Experimental Method | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Thermocouples | Relatively simple, inexpensive | Point measurements, can disturb the flow field |

| Heat Flux Sensors | Direct measurement of heat flux | Can be intrusive, calibration challenges |

| Infrared Thermography | Non-intrusive, provides surface temperature maps | Can be affected by surface emissivity variations |

| Liquid Crystal Thermography | Visualizes temperature distribution, relatively low cost | Limited temperature range, surface preparation needed |

- Advantages of Experimental Methods:

- Provides real-world data, accounting for complexities not easily captured in analytical models.

- High accuracy when properly executed.

- Disadvantages of Experimental Methods:

- Can be expensive and time-consuming.

- Results are specific to the experimental setup and may not be easily generalized.

- Analytical/Numerical Methods:

These methods rely on empirical correlations and theoretical models derived from fundamental principles of fluid mechanics and heat transfer.

- Empirical Correlations: Numerous correlations exist for various flow regimes (laminar, turbulent), geometries (flat plate, pipe flow, etc.), and fluid properties. These correlations are often derived from experimental data and are typically expressed in dimensionless numbers like the Nusselt number (Nu), Reynolds number (Re), and Prandtl number (Pr).

- Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD): CFD offers a powerful numerical approach to solving the governing equations of fluid flow and heat transfer. It allows for detailed analysis of complex geometries and flow conditions, providing insights into temperature distributions, velocity fields, and heat transfer coefficients.

- Advantages of Analytical/Numerical Methods:

- Cost-effective compared to experiments.

- Can explore a wider range of parameters and design variations.

- Applicable to complex geometries that are difficult to study experimentally.

- Disadvantages of Analytical/Numerical Methods:

- Relies on assumptions and simplifications.

- Accuracy depends on the validity of the chosen model and the quality of the mesh (for CFD).

Factors Influencing Heat Transfer Coefficients:

The convective heat transfer coefficient is influenced by a multitude of factors:

- Fluid Properties:

- Thermal Conductivity (k): Higher thermal conductivity leads to higher heat transfer coefficients.

- Viscosity (μ): Higher viscosity hinders heat transfer, resulting in lower coefficients.

- Specific Heat (cp): Influences the fluid’s capacity to store thermal energy.

- Density (ρ): Affects the flow patterns and thus the heat transfer coefficient.

- Flow Regime: Turbulent flow typically results in significantly higher heat transfer coefficients compared to laminar flow due to enhanced mixing and momentum transfer.

- Flow Velocity (V): Higher flow velocities generally lead to higher heat transfer coefficients.

- Surface Geometry: Surface roughness, shape, and orientation can influence the flow patterns and boundary layer characteristics, thereby affecting the heat transfer coefficient.

- Temperature Difference (ΔT): The temperature difference between the fluid and the surface is the driving force for heat transfer, and in some cases, the heat transfer coefficient can be temperature-dependent.

Impact on Heat Exchanger Design:

Heat transfer coefficients are crucial for heat exchanger design and performance evaluation.

- Size and Effectiveness: Higher heat transfer coefficients allow for smaller heat exchanger sizes for the same heat duty, reducing material costs and space requirements. They also contribute to higher effectiveness, which represents the ratio of actual heat transfer to the maximum possible heat transfer.

- Optimization: Understanding how different factors influence the heat transfer coefficient allows engineers to optimize heat exchanger design for maximum performance and efficiency. This might involve selecting appropriate materials, optimizing flow geometries, or enhancing turbulence.

The accurate determination and manipulation of heat transfer coefficients are paramount for optimizing thermal systems and achieving desired performance targets. They form the cornerstone of successful heat exchanger design and are essential for a wide array of engineering applications.

Heat Exchangers: Design Principles and CFD Simulations

Heat exchangers are devices specifically engineered to facilitate efficient heat transfer between two or more fluids at different temperatures without allowing them to mix. They are ubiquitous in various engineering applications, including power generation, HVAC systems, chemical processing, refrigeration, and electronics cooling. Effective heat exchanger design requires careful consideration of several factors, including fluid properties, flow rates, temperature requirements, and pressure drop limitations. Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) plays a crucial role in optimizing heat exchanger performance and predicting their behavior under various operating conditions.

Types of Heat Exchangers:

Several heat exchanger designs exist, each optimized for specific applications:

- Shell-and-Tube Heat Exchangers: These are the most common type, consisting of a shell containing a bundle of tubes. One fluid flows through the tubes, while the other flows through the shell, exchanging heat across the tube walls.

- Plate Heat Exchangers: These exchangers utilize a series of thin, corrugated plates to create channels for the two fluids. The plates provide a large surface area for heat transfer, making them compact and efficient.

- Finned-Tube Heat Exchangers: These exchangers use fins attached to the tubes to increase the surface area for heat transfer, particularly effective when one fluid has a significantly lower heat transfer coefficient (e.g., air).

- Regenerative Heat Exchangers: These exchangers alternately store and release heat from a thermal storage material. Fluids flow through the same passage, alternately heating and cooling the storage material.

- Compact Heat Exchangers: These are highly efficient, small-volume exchangers designed for specialized applications where space and weight are critical constraints.

| Heat Exchanger Type | Description | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Shell-and-Tube | Shell contains tube bundle; fluids flow separately through shell and tubes | Robust, high-pressure capability | Can be bulky, lower heat transfer rate compared to PHE |

| Plate | Series of corrugated plates form channels for fluid flow | Compact, high efficiency, easy to clean | Lower pressure capability, potential for leaks |

| Finned-Tube | Fins attached to tubes increase surface area | Enhanced heat transfer for fluids with low h | Higher pressure drop, can be difficult to clean |

| Regenerative | Thermal storage material alternately heated and cooled by fluids | High efficiency, can handle large temperature differences | Complex design, potential for cross-contamination |

CFD Simulations in Heat Exchanger Design:

Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) software, such as ANSYS, has become an indispensable tool for optimizing heat exchanger design and performance. CFD simulations provide detailed insights into the complex flow and heat transfer phenomena occurring within the exchanger.

- Benefits of CFD Simulations:

- Visualization of Flow Patterns: CFD allows engineers to visualize flow distributions, identify areas of recirculation, stagnation, or bypass flow, and optimize flow paths for uniform distribution and enhanced heat transfer.

- Prediction of Temperature Distributions: CFD predicts temperature profiles within the fluids and the solid components of the heat exchanger. This information is crucial for identifying hot spots, cold spots, and evaluating the overall thermal performance.

- Evaluation of Pressure Drop: CFD calculates pressure drop across the heat exchanger, enabling engineers to minimize pressure losses and optimize pumping power requirements.

- Parametric Studies: CFD allows engineers to perform parametric studies to investigate the effects of various design parameters, such as tube diameter, fin spacing, baffle arrangement, and flow rates, on the heat exchanger performance.

- Virtual Prototyping: CFD simulations enable virtual prototyping, allowing engineers to test and optimize designs before physical prototypes are built, saving time and cost.

For a deeper dive into ANSYS, check out our blog post on what is ansys.

Optimization Strategies using CFD:

- Baffle Optimization: In shell-and-tube exchangers, baffles are used to direct the shell-side fluid flow and enhance heat transfer. CFD can be used to optimize baffle spacing and geometry to maximize heat transfer while minimizing pressure drop.

- Fin Design Optimization: CFD can be used to optimize fin geometry, spacing, and material to maximize heat transfer from the finned surface.

- Flow Distribution Optimization: CFD helps identify and correct flow maldistribution issues, ensuring uniform flow distribution across the heat exchanger and maximizing its effectiveness.

- Material Selection: CFD simulations can assist in evaluating the thermal performance of different materials for heat exchanger components, aiding in material selection for optimal performance and cost-effectiveness.

CFD simulations provide invaluable insights for designing efficient and reliable heat exchangers. Now, let’s explore how these principles apply in various engineering systems.

Understanding Heat Transfer in Various Systems (HVAC, Power Generation, Electronics)

Heat transfer principles are fundamental to a vast array of engineering systems and play a critical role in their design, operation, and optimization. From the comfort of our homes to the generation of electricity and the reliability of electronic devices, heat transfer phenomena are ubiquitous and essential. Let’s explore the application of these principles in three key sectors: HVAC, Power Generation, and Electronics.

HVAC Systems:

Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning (HVAC) systems rely heavily on heat transfer principles to maintain comfortable indoor environments. Efficient HVAC design requires careful consideration of all three modes of heat transfer:

- Conduction: Heat transfer through the building envelope (walls, roof, windows) is primarily governed by conduction. Insulation materials with low thermal conductivity are used to minimize heat transfer and improve energy efficiency.

- Convection: Forced convection is used to circulate air within the building and transfer heat to or from the occupied space. The design of air ducts, diffusers, and fans plays a crucial role in optimizing airflow and heat distribution.

- Radiation: Radiant heating and cooling systems utilize radiation to transfer heat directly to or from surfaces within the building.

- Case Study: Efficient Air Conditioning System Design: Designing an efficient air conditioning system involves optimizing several heat transfer processes:

- Heat Exchange in the Condenser and Evaporator: The efficiency of the refrigerant cycle depends on effective heat transfer in the condenser (rejecting heat to the outdoors) and the evaporator (absorbing heat from the indoors). Finned-tube heat exchangers are commonly used in these components to enhance heat transfer.

- Airflow Management: Proper airflow management within the building is crucial for effective cooling. This involves optimizing ductwork design, diffuser placement, and fan selection to ensure uniform temperature distribution and minimize energy consumption.

- Building Envelope Considerations: Minimizing heat transfer through the building envelope through proper insulation and window selection is essential for reducing the cooling load and improving overall system efficiency.

Power Generation:

Heat transfer is at the heart of power generation processes, particularly in thermal power plants.

- Combustion: The combustion process converts chemical energy into thermal energy, generating high-temperature gases.

- Heat Transfer to Working Fluid: The heat generated during combustion is transferred to a working fluid (typically water or steam) in a boiler or heat exchanger.

- Turbine Operation: The high-temperature, high-pressure working fluid expands through a turbine, converting thermal energy into mechanical energy to drive a generator.

- Condensation: The working fluid is then condensed, rejecting heat to a cooling system, and the cycle repeats.

- Case Study: Power Plant Optimization: Optimizing power plant efficiency involves maximizing heat transfer rates in key components:

- Boiler Design: Maximizing heat transfer from the combustion gases to the working fluid in the boiler is crucial for overall plant efficiency. This involves optimizing the boiler geometry, tube arrangement, and flow rates.

- Turbine Blade Cooling: Turbine blades are exposed to extremely high temperatures. Effective cooling of the blades is essential for maintaining their structural integrity and extending their lifespan. Internal cooling passages and film cooling techniques are employed to manage blade temperatures.

- Condenser Optimization: Efficient heat rejection in the condenser is crucial for maintaining a low back pressure and maximizing the work output of the turbine.

Electronics Cooling:

Effective heat dissipation is paramount in electronics to prevent overheating and ensure the reliability and longevity of electronic components.

- Conduction: Heat generated within electronic components is conducted through the device packaging and to heat sinks.

- Convection: Heat sinks utilize natural or forced convection to transfer heat to the surrounding air.

- Radiation: While generally a smaller contributor, radiation can also play a role in heat dissipation, particularly for high-temperature components.

- Case Study: Heat Sink Design for Electronic Components: Designing effective heat sinks requires optimizing various factors:

- Material Selection: Materials with high thermal conductivity, such as aluminum and copper, are commonly used for heat sinks.

- Fin Geometry: Optimizing fin geometry (height, thickness, spacing) maximizes the surface area for convective heat transfer.

- Airflow Management: Forced convection using fans can significantly enhance heat transfer from the heat sink. Proper fan placement and airflow management are crucial for maximizing cooling performance.

These examples demonstrate the pervasive influence of heat transfer across diverse industries. Understanding and effectively managing heat transfer processes is essential for designing efficient, reliable, and sustainable engineering systems. Let’s delve into some advanced topics, including phase change and extended surfaces.

Advanced Topics in Heat Transfer: Phase Change and Extended Surfaces

While conduction, convection, and radiation represent the fundamental modes of heat transfer, more complex phenomena like phase change and the use of extended surfaces play critical roles in many engineering applications. These advanced topics offer opportunities for significantly enhancing heat transfer rates and optimizing thermal system performance.

Phase Change (Mass Transfer) Heat Transfer:

Phase change processes, including boiling and condensation, involve substantial heat transfer due to the absorption or release of latent heat.

- Boiling: Boiling occurs when a liquid transforms into a vapor at its saturation temperature. The process absorbs latent heat of vaporization, resulting in significant heat transfer. Different boiling regimes exist, each with distinct characteristics and heat transfer coefficients:

- Nucleate Boiling: Characterized by the formation of bubbles on the heated surface.

- Transition Boiling: A less stable regime with fluctuating heat transfer rates.

- Film Boiling: A vapor film forms on the heated surface, insulating it and reducing heat transfer.

- Condensation: Condensation is the reverse process of boiling, where a vapor transforms into a liquid, releasing latent heat of condensation. Two main types of condensation occur:

- Film Condensation: A continuous film of liquid forms on the cooled surface.

- Dropwise Condensation: Discrete droplets form on the cooled surface, offering higher heat transfer rates compared to film condensation.

| Phase Change Process | Description | Heat Transfer Characteristics | Applications |

| Boiling | Liquid transforms to vapor, absorbing latent heat | High heat transfer rates, dependent on boiling regime | Power generation, refrigeration, chemical processing |

| Condensation | Vapor transforms to liquid, releasing latent heat | High heat transfer rates, dropwise condensation is more efficient | Power generation, HVAC, chemical processing |

Understanding and controlling the boiling and condensation processes are crucial for optimizing the performance of various thermal systems, including power plants, refrigeration systems, and chemical processing equipment.

Extended Surfaces (Fins):

Extended surfaces, commonly known as fins, are used to enhance heat transfer by increasing the surface area available for convection. They are particularly effective when the heat transfer coefficient of one of the fluids is relatively low (e.g., air).

- Fin Design Considerations:

- Fin Material: Materials with high thermal conductivity, such as aluminum and copper, are preferred for efficient heat transfer.

- Fin Geometry: Fin shape, length, thickness, and spacing are carefully optimized to maximize surface area while minimizing material usage and pressure drop. Common fin types include straight fins, pin fins, and annular fins.

- Fin Efficiency: Fin efficiency represents the ratio of actual heat transfer from the fin to the maximum possible heat transfer if the entire fin were at the base temperature.

- Applications of Fins:

- Air-Cooled Heat Exchangers: Fins are extensively used in air-cooled heat exchangers to enhance heat transfer from the hot fluid to the air.

- Electronic Cooling: Heat sinks with fins are essential for dissipating heat from electronic components.

- Internal Combustion Engines: Fins are used on engine cylinders and radiators to dissipate heat to the surrounding air.

| Fin Parameter | Effect on Heat Transfer |

| Material | Higher thermal conductivity leads to better heat transfer |

| Length | Longer fins increase surface area, but can decrease efficiency |

| Thickness | Thicker fins increase conduction, but add weight and cost |

| Spacing | Optimal spacing maximizes overall heat transfer |

Understanding phase change and extended surfaces is essential for optimizing a wide range of thermal systems. Now, let’s explore the practical application of CFD in heat transfer analysis.

CFD in Heat Transfer Analysis: A Practical Guide

Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) has revolutionized the field of heat transfer analysis, providing engineers with a powerful tool to simulate and understand complex thermal phenomena. CFD software, such as ANSYS Fluent, Star-CCM+, and COMSOL, allows for detailed modeling of fluid flow and heat transfer in intricate geometries and under various operating conditions. This enables engineers to optimize designs, predict performance, and troubleshoot thermal issues before physical prototypes are built.

Key Steps in a CFD Analysis:

A typical CFD analysis involves the following key steps:

- Geometry Creation: The first step involves creating a 3D model of the system or component being analyzed. This can be done using CAD software or dedicated geometry creation tools within the CFD software.

- Mesh Generation: Mesh generation is a crucial step where the computational domain is divided into smaller elements (cells or elements). The quality of the mesh significantly impacts the accuracy and stability of the simulation. Different meshing strategies exist, including structured meshes, unstructured meshes, and hybrid meshes.

- Mesh Refinement: In areas with complex flow features or high gradients, mesh refinement is essential to capture the details accurately. Techniques like adaptive mesh refinement automatically refine the mesh based on solution variables.

- Solver Settings: Defining appropriate solver settings is critical for obtaining accurate and reliable results. This includes selecting:

- Turbulence Models: Choosing the right turbulence model depends on the flow regime (laminar or turbulent) and the complexity of the flow. Common turbulence models include k-ε, k-ω, and Reynolds Stress Models (RSM).

- Boundary Conditions: Accurate boundary conditions are essential for representing the physical environment of the simulation. This includes specifying inlet and outlet conditions, wall temperatures, heat fluxes, and other relevant parameters.

- Numerical Schemes: Different numerical schemes are available for discretizing and solving the governing equations. The choice of scheme affects the accuracy and stability of the solution.

- Solution and Monitoring: The simulation is run using the chosen solver, and the solution is monitored for convergence. Convergence criteria are defined to ensure that the solution has reached a steady state or a stable time-dependent solution.

- Post-Processing and Visualization: Once the simulation is complete, the results are post-processed and visualized to extract meaningful information. This includes analyzing temperature distributions, velocity fields, pressure drops, heat fluxes, and other relevant parameters.

| CFD Step | Description | Key Considerations |

| Geometry Creation | Creating the 3D model of the system | Accuracy and detail of the geometry |

| Mesh Generation | Discretizing the domain into smaller elements | Mesh quality, refinement in critical areas |

| Solver Settings | Defining turbulence models, boundary conditions, numerical schemes | Appropriate model selection based on flow regime and complexity |

| Solution | Running the simulation and monitoring convergence | Convergence criteria, computational resources |

| Post-Processing | Analyzing and visualizing the results | Extracting relevant data, generating informative visualizations |

You can explore more about CFD and its applications in our blog post what is CFD. For specialized CFD services and consulting, you can visit our dedicated pages: CFD Services and CFD Consulting.

Benefits of Using CFD in Heat Transfer Analysis:

- Detailed Insights: CFD provides detailed insights into temperature distributions, flow patterns, and heat transfer rates, which are difficult to obtain through experimental methods alone.

- Optimization Potential: CFD allows for virtual prototyping and parametric studies, enabling engineers to optimize designs for improved heat transfer performance, reduced pressure drop, and minimized material usage.

- Cost and Time Savings: By identifying and resolving thermal issues early in the design process, CFD can significantly reduce the need for expensive physical prototypes and experimental testing, saving both time and cost.

- Enhanced Understanding: CFD simulations provide a deeper understanding of complex heat transfer phenomena, allowing engineers to make informed design decisions and develop innovative solutions.

CFD empowers engineers to gain deep insights into heat transfer processes, leading to optimized designs and improved performance. Finally, let’s address some common challenges encountered in heat transfer applications.

Troubleshooting Common Heat Transfer Problems

Common challenges in heat transfer applications include non-uniform heat fluxes, thermal stresses, and fouling in heat exchangers. Practical solutions involve optimizing the geometry of heat transfer surfaces, selecting appropriate materials, and implementing effective cleaning procedures for heat exchangers. MR CFD experts can provide valuable insights and solutions for these complex issues.

Addressing these challenges is crucial for ensuring the efficient and reliable operation of thermal systems. Now, let’s look towards the future of heat transfer.

Future of Heat Transfer: Innovative Applications and Research

The field of heat transfer is constantly evolving, driven by the need for more efficient and sustainable thermal management solutions. Research areas include micro and nanoscale heat transfer, advanced materials for thermal management, and innovative heat exchanger designs. These advancements hold immense promise for addressing critical challenges in various sectors, from energy generation to electronics cooling.

The future of heat transfer is bright, with exciting advancements on the horizon. MR CFD remains at the forefront of these developments, offering cutting-edge CFD consulting and services to help clients optimize their thermal systems and achieve their engineering goals.

Comments (0)